Hi guys. This is just a quick note to let you know I'll be joining the folks at Macro Business. If you haven't seen the site yet, it's a "superblog" with some of Australia's best bloggers covering the economics and finance world in Australia and beyond.

Since the team already has several very talented people writing about Australia, and since I'm currently based in New York, I'm going to change my focus a bit and give my perspective on what's going on in the US. The main focus will be the economy and financial markets, but I will also delve into politics and possibly other important issues like who wore the best outfit to the Oscars. In any case, you can read my first post here.

As for this humble blog, I will keep it alive for now, and may post occasionally if I have anything to say about Australia. Since I have a day job, it's likely to be sporadic at best though. Thanks to all the readers and commenters so far, and please hop over to Macro Business and check it out.

Cheers

Monday, January 24, 2011

Sunday, January 23, 2011

Disaster myopia: floods and financial crises

Apart from the tragic loss of life, one of the saddest outcomes of the Queensland floods is the financial ruin that hundreds if not thousands of families are now facing having had their properties destroyed. Many do not have flood insurance. This recent article in The Age tells one typical story.

Disaster Myopia

This is a classic example of what economists and psychologists call "disaster myopia" -- the tendency of people to greatly underestimate the chance of catastrophic events. Here's how it works. You get a big disaster, say the 1974 floods in Queensland. This serves as a wake up call for people that bad things can and do happen. For a while, they start to behave more prudently: more people take out flood insurance, builders become wary of building in vulnerable areas, and banks start to take into account the flood vulnerability of houses before they issue mortgages. But sooner or later, memories of the disaster start to fade. As the years pass, fewer and fewer people bother getting flood insurance. Developments start cropping up closer and closer to river banks. Banks stop worrying about flood risk and issue loans to whoever is willing. We all get a bit complacent. And then another disaster strikes...

On a broader scale, this phenomenon is exactly what has got much of the global economy in such a big mess since 2008. In fact, the risky behaviour by banks that was at the heart of the recent global financial crisis can basically be seen as the result of disaster myopia, Andrew Haldane of the Bank of England has argued. After a "golden decade" of high economic growth, rising house prices and low inflation around most of the world in the 2000s, banks started lowering their lending standards, based on the idea that the world had entered a new phase of economic stability. After all, there hadn't been a major global financial shock for about a decade, the period of time that seems to mark the limits of the attention span of risk managers in banks, Haldane notes:

Apologies if this is bringing back nightmares of Statistics 101, but you can see here that the probability distributions for both of these indicators looked very different in the "golden decade" to the longer-term history: in statistical terms, there was not a lot of variance around the mean. What did this lead to in practice?

If you were a banker with a short memory and only looked at the yellow curve, you might have concluded that property lending was very safe, because unemployment was "permanently" low and therefore the risk of borrowers defaulting on their loans was negligible. And bankers have an incentive to have short memories. After all, if everything blows up in 10 years because of all the stupid loans you made, who cares, because you still get to keep all the big bonuses you've made in the meantime.

And if you were an investor looking at the yellow curves above, you might have concluded that stocks were a very safe investment, because corporate earnings were growing steadily with very little volatility. This illusion of stability led to an underpricing of risk: people took on a lot of debt and pushed asset prices higher and higher. And then the US subprime crisis hit and markets all over the world came crashing down.

ANZ's Gold Medal

It's time to return this discussion to Australia, where disaster myopia is almost an art form in some circles. A wonderful example of this came from a report by ANZ last week, which was their latest attempt to justify the sky high level of Australian property prices. I'm not going to examine it in detail, because other bloggers have already done an excellent job at ripping their arguments to shreds (see here for example). However, I do want to pick up on the paragraph below from this summary of ANZ's view.

Let's deal with ANZ's second point first. Montalti points to the low level of delinquencies in Australia and says that this is evidence that the market is valued correctly. With all due respect to Mr Montalti, this is one of the dumbest arguments I have heard in a long time. It's a bit like if a meteorologist had told you at the end of 2010 that there hasn't been a major flood in Queensland for 30 years, so there was "evidence" to prove that nobody ever needs to worry about the risk of floods anymore.

In any case, back to ANZ's first point, which is almost as silly. What they're telling us here is that the very high level of house prices in Australia is justified because the historical decline in interest rates (in one previous report they described this decline as "permanent") allows people to service a much higher amount of debt than in the past. And they're not the only ones making this argument. The IMF recently cited "permanently lower nominal interest rates that have occurred since 2000" in its analysis of Australian house prices.

But what if the low level of interest rates we've seen in Australia over the past decade isn't permanent? In fact, it would be very surprising if it was anything more than temporary. Below, you can see that I've charted the probability distribution of Australian interest rates along the lines of the Bank of England charts above. (I picked the 90-day rate because the RBA provides data for this one all the way back to 1969)

The result is quite interesting. If you only looked at the past decade, represented by the grey bars, you would see a nice bell-shaped looking distribution with interest rates generally clustered in the 5-7% range. But the red line, which shows the distribution of interest rates from 1969 to today, shows you that the past decade has been a bit of an anomaly in historical terms. The distribution is heavily skewed to the right.

Does this mean that interest rates are going to go back to 15% like we had in the 1970s? No it doesn't. But what it does suggest is that if you think the relatively stable level of interest rates we've had in the past decade is some kind of "new normal", you're probably in for a rude shock at some point in the future. And that's a bit of a problem, because Australian house prices today are so high that many borrowers are already forced to devote an uncomfortably high portion of their disposable incomes to mortgage payments even with rates at current levels.

How many people could deal with a rise in mortgage rates to 10%? Again, not to say that this is likely, simply that it wouldn't be all that out of the ordinary in historical terms.

A margin of safety

It might sound like the tone of this post is overly pessimistic. After all, if we became totally paranoid about all the possible disasters that could happen none of us would even leave the house every day. And we wouldn't take any kind of financial risks at all. But that's not really the point. The point is that when making financial decisions, we should allow for the fact that some of the assumptions we have about the world could quite possibly turn out to be wrong. For example, ideas like:

Oh, by the way, I didn't mention the risk that the earth might get hit by a massive asteroid in 2014, but I can assure you there's nothing to worry about there.

Until next time.

Landlords across Queensland are likely to go bankrupt in the next few months, an industry expert has warned...Now, I have nothing but sympathy for the people involved. But you do have to ask the question. How sensible is it to have your entire net wealth tied up in six rental properties that are all geographically concentrated in a single flood prone area? And on top of that, to not bother getting flood insurance?

Paul and Sarah Smith had been renting Sarah’s mother’s rental property at Goodna when the floods hit. Their home was inundated to the second story and the damage is enormous.

Ms Smith said her mother owned five other properties in Goodna which she rented out – all of them had gone under in the flood last week.

“My mum has six rental houses and they’re all ruined,” Ms Smith said.

“You might say ‘oh she’s got six rental properties, she must be rich’, but she’s not – she has mortgages on all of them and relies on the rent to help pay.

“How will she pay for them now? She’s devastated. She doesn’t have insurance for this...”

Disaster Myopia

This is a classic example of what economists and psychologists call "disaster myopia" -- the tendency of people to greatly underestimate the chance of catastrophic events. Here's how it works. You get a big disaster, say the 1974 floods in Queensland. This serves as a wake up call for people that bad things can and do happen. For a while, they start to behave more prudently: more people take out flood insurance, builders become wary of building in vulnerable areas, and banks start to take into account the flood vulnerability of houses before they issue mortgages. But sooner or later, memories of the disaster start to fade. As the years pass, fewer and fewer people bother getting flood insurance. Developments start cropping up closer and closer to river banks. Banks stop worrying about flood risk and issue loans to whoever is willing. We all get a bit complacent. And then another disaster strikes...

On a broader scale, this phenomenon is exactly what has got much of the global economy in such a big mess since 2008. In fact, the risky behaviour by banks that was at the heart of the recent global financial crisis can basically be seen as the result of disaster myopia, Andrew Haldane of the Bank of England has argued. After a "golden decade" of high economic growth, rising house prices and low inflation around most of the world in the 2000s, banks started lowering their lending standards, based on the idea that the world had entered a new phase of economic stability. After all, there hadn't been a major global financial shock for about a decade, the period of time that seems to mark the limits of the attention span of risk managers in banks, Haldane notes:

As time passes, convincing the crowds that you are not naked becomes progressively easier. It is perhaps no coincidence that the last three truly systemic crises – October 1987, August 1998, and the credit crunch which commenced in 2007 – were roughly separated by a decade.The problem is, the "golden decade" that banks were basing their decision making on, was a highly unusual one compared to history, as the two displays of UK unemployment and corporate earnings growth show below.

|

| Source: Bank of England |

If you were a banker with a short memory and only looked at the yellow curve, you might have concluded that property lending was very safe, because unemployment was "permanently" low and therefore the risk of borrowers defaulting on their loans was negligible. And bankers have an incentive to have short memories. After all, if everything blows up in 10 years because of all the stupid loans you made, who cares, because you still get to keep all the big bonuses you've made in the meantime.

And if you were an investor looking at the yellow curves above, you might have concluded that stocks were a very safe investment, because corporate earnings were growing steadily with very little volatility. This illusion of stability led to an underpricing of risk: people took on a lot of debt and pushed asset prices higher and higher. And then the US subprime crisis hit and markets all over the world came crashing down.

ANZ's Gold Medal

It's time to return this discussion to Australia, where disaster myopia is almost an art form in some circles. A wonderful example of this came from a report by ANZ last week, which was their latest attempt to justify the sky high level of Australian property prices. I'm not going to examine it in detail, because other bloggers have already done an excellent job at ripping their arguments to shreds (see here for example). However, I do want to pick up on the paragraph below from this summary of ANZ's view.

A new report from ANZ claims residential properties aren't overvalued and has taken aim at traditional methods of evaluating affordability, including price-to-income ratios, saying they don't take into account more complicated and less-quantifiable factors including historic declines in interest rates... More importantly, (ANZ economist) Montalti says, is how the market is performing now and where those prices are actually moving. He points out the country has quite a low delinquency rate, which is evidence of a largely affordable market that is valued correctly.In this single paragraph, ANZ gives us two classic examples of disaster myopia.

Let's deal with ANZ's second point first. Montalti points to the low level of delinquencies in Australia and says that this is evidence that the market is valued correctly. With all due respect to Mr Montalti, this is one of the dumbest arguments I have heard in a long time. It's a bit like if a meteorologist had told you at the end of 2010 that there hasn't been a major flood in Queensland for 30 years, so there was "evidence" to prove that nobody ever needs to worry about the risk of floods anymore.

In any case, back to ANZ's first point, which is almost as silly. What they're telling us here is that the very high level of house prices in Australia is justified because the historical decline in interest rates (in one previous report they described this decline as "permanent") allows people to service a much higher amount of debt than in the past. And they're not the only ones making this argument. The IMF recently cited "permanently lower nominal interest rates that have occurred since 2000" in its analysis of Australian house prices.

But what if the low level of interest rates we've seen in Australia over the past decade isn't permanent? In fact, it would be very surprising if it was anything more than temporary. Below, you can see that I've charted the probability distribution of Australian interest rates along the lines of the Bank of England charts above. (I picked the 90-day rate because the RBA provides data for this one all the way back to 1969)

The result is quite interesting. If you only looked at the past decade, represented by the grey bars, you would see a nice bell-shaped looking distribution with interest rates generally clustered in the 5-7% range. But the red line, which shows the distribution of interest rates from 1969 to today, shows you that the past decade has been a bit of an anomaly in historical terms. The distribution is heavily skewed to the right.

Does this mean that interest rates are going to go back to 15% like we had in the 1970s? No it doesn't. But what it does suggest is that if you think the relatively stable level of interest rates we've had in the past decade is some kind of "new normal", you're probably in for a rude shock at some point in the future. And that's a bit of a problem, because Australian house prices today are so high that many borrowers are already forced to devote an uncomfortably high portion of their disposable incomes to mortgage payments even with rates at current levels.

How many people could deal with a rise in mortgage rates to 10%? Again, not to say that this is likely, simply that it wouldn't be all that out of the ordinary in historical terms.

A margin of safety

It might sound like the tone of this post is overly pessimistic. After all, if we became totally paranoid about all the possible disasters that could happen none of us would even leave the house every day. And we wouldn't take any kind of financial risks at all. But that's not really the point. The point is that when making financial decisions, we should allow for the fact that some of the assumptions we have about the world could quite possibly turn out to be wrong. For example, ideas like:

- Property prices in Australia double every seven years

- Unemployment under 5% is the norm for Australia

- The terms of trade boost from China will last for decades

- Interest rates will never go as high as 10% again

Oh, by the way, I didn't mention the risk that the earth might get hit by a massive asteroid in 2014, but I can assure you there's nothing to worry about there.

Until next time.

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Iron ore and Australian house prices

In my previous post, we started to examine the million dollar question for Australia's economy today. How long will China's rapid growth and the commodity price boom last? We noted that while the arguments for continued growth in commodity demand from China appear fairly plausible, there are significant risks in the near term. And in actual fact, we've greatly understated the risks to Australia's terms of trade so far in this discussion, because we haven't even looked at what is happening on the supply side of commodities.

Commodity Supply 101

The supply of commodities like iron ore or coal tends to be fairly "inelastic" -- or unresponsive -- to rising demand in the short run. This is because there are massive capital costs involved in expanding mining operations or exploiting new reserves. Unlike agricultural commodities like potatoes, the average punter can't just start digging up iron ore in the back yard and selling it on international markets.

What this means is that when you get a surge of demand in commodities, supply doesn't rise by much in the short term, so prices shoot through the roof and the miners make boatloads of money. But what history shows is that commodity prices repeat long cycles of boom and bust. When prices get high enough, miners eventually find it more economical to add new capacity and expand supply. There's generally a lag until this new supply hits the market, but when it does, prices inevitably cool down again. And that's exactly what we are likely to see over the next few years.

The chart below from Global Mining Investments illustrates the economics of this very well. This is the cost curve for various iron ore producers around the world. I'm focusing on iron ore because, along with coal, it's Australia's biggest export.

You can see that the big three of Rio Tinto, Vale and BHP Billiton can make money as long as prices stay above $30-40 a tonne, around $100 below the current market price. This is because the big three, who control around two thirds of the market, have access to some of the world's highest grade iron ore deposits -- places like the Pilbara in Western Australia and Carajas in Brazil. So it's no wonder they're making a killing. But as the price of iron ore keeps rising, it becomes economical for higher cost producers in places like India and China to start tapping their lower grade iron ore deposits.

A Coming Iron-Ore Glut?

In fact, one recent report says there could be an enormous 685 million tonnes of new iron ore production capacity coming on stream between 2010 and 2012, which is roughly equal to what Australia and Brazil (the worlds two biggest producers) produced together in 2009. For a list of some of these projects, see here. Furthermore, China has been speeding up the exploitation of domestic deposits and buying up mines all over the world to help ease their dependence on the big three. From a recent article by Stephen Bartholomeusz in Business Spectator:

And this new supply will also be hitting the market at a time when some economists (read Michael Pettis, for example) believe China is running into some serious constraints in its growth model. If China was to hit a speedbump some time in the coming few years and fall into recession, there is a chance that commodity prices could collapse, with disastrous consequences for Australia. This is not necessarily a likely scenario, but it is a risk that we need to be mindful of, because Australia's economy is extremely vulnerable to such a potential shock, as we will examine a bit further below.

Australia: Living on Borrowed Time

Let's go full circle back to the terms of trade. Some of you might have read reports of a recent study by the IMF, which surprisingly concluded that Australian house prices were only mildly overvalued. The IMF argued that there were solid fundamental reasons for Australia having the most expensive property prices in the world. And one of the key reasons they cited is the massive rise in Australia's terms of trade.

You can see from the chart below that, indeed, inflation-adjusted house prices have basically increased in line with Australia's terms of trade over the past two decades.

This raises an obvious question. If you agree with the IMF's logic, doesn't this imply that house prices have to fall when the once in a generation boost to the terms of trade reverses?

Now, Australia's terms of trade has gone through long rises and falls over history without huge problems. And a decline in the terms of trade wouldn't necessarily have to be a big problem if Australia had invested the proceeds of the current boom productively. But instead, Australians have turbocharged the boom by taking on record levels of personal debt (see below), mainly to purchase houses. And the Australian banks are financing a good part of this mortgage debt not through deposits, but through a potentially unstable source of funding: the international bond markets.

So we are now left very highly leveraged, and the valuation of the biggest asset that most Australians own (their houses and investment properties) as well as their ability to service this debt (and the banks' willingness to keep extending credit) is dependent on the continuation of the commodity boom. The enormous level of personal debt means that many Australians today are highly vulnerable to potential shocks in the economy, whether from a slowdown in China, or from higher interest rates.

The chart below, from an excellent post at deflationite.com, shows just how unbalanced the Australian economy has become over the past two decades. You can see that in 1990, the majority of Australian bank lending was being channeled into business investment, or investment in Australia's future productive capacity. But over the past two decades, the portion of bank credit allocated to business investment has steadily shrunk. In place of this, we have seen massive growth in property-related lending, to the point where one in seven Australians today owns one or more investment properties.

In essence, Australians have been behaving as if the commodity boom and the days of easy credit will last forever. Nobody can predict the timing, but they won't. Now, that doesn't have to mean disaster, but we're kidding ourselves if we think the adjustment is going to be easy.

As Warren Buffet once said, "It's only when the tide goes out that you learn who's been swimming naked."

Commodity Supply 101

The supply of commodities like iron ore or coal tends to be fairly "inelastic" -- or unresponsive -- to rising demand in the short run. This is because there are massive capital costs involved in expanding mining operations or exploiting new reserves. Unlike agricultural commodities like potatoes, the average punter can't just start digging up iron ore in the back yard and selling it on international markets.

What this means is that when you get a surge of demand in commodities, supply doesn't rise by much in the short term, so prices shoot through the roof and the miners make boatloads of money. But what history shows is that commodity prices repeat long cycles of boom and bust. When prices get high enough, miners eventually find it more economical to add new capacity and expand supply. There's generally a lag until this new supply hits the market, but when it does, prices inevitably cool down again. And that's exactly what we are likely to see over the next few years.

The chart below from Global Mining Investments illustrates the economics of this very well. This is the cost curve for various iron ore producers around the world. I'm focusing on iron ore because, along with coal, it's Australia's biggest export.

You can see that the big three of Rio Tinto, Vale and BHP Billiton can make money as long as prices stay above $30-40 a tonne, around $100 below the current market price. This is because the big three, who control around two thirds of the market, have access to some of the world's highest grade iron ore deposits -- places like the Pilbara in Western Australia and Carajas in Brazil. So it's no wonder they're making a killing. But as the price of iron ore keeps rising, it becomes economical for higher cost producers in places like India and China to start tapping their lower grade iron ore deposits.

|

| Source: GMI |

A Coming Iron-Ore Glut?

In fact, one recent report says there could be an enormous 685 million tonnes of new iron ore production capacity coming on stream between 2010 and 2012, which is roughly equal to what Australia and Brazil (the worlds two biggest producers) produced together in 2009. For a list of some of these projects, see here. Furthermore, China has been speeding up the exploitation of domestic deposits and buying up mines all over the world to help ease their dependence on the big three. From a recent article by Stephen Bartholomeusz in Business Spectator:

The notion of a prolonged ‘mother of all booms’ is ... not one that the big miners necessarily subscribe to. They are aware that the mid-sized and smaller iron ore and coal producers, after something of a hiatus during the crisis, are now scrambling to bring their production into the market. There will be big and continuing increases in supply to discipline the prices... Goldman Sachs’ resource analysts suggested earlier this week that the iron ore market could move into balance in 2013 and over-supply as early as 2014. Even if steel production in China continues to grow at current rates the market would still be in an over-supplied position by 2015, they said.Meanwhile, iron ore spot prices continue to grind higher, and are currently approaching $180 a tonne. But a growing number of analysts are warning that this rise is unsustainable, and that a fall back well below $100 is inevitable in coming years. From another recent report in Barrons:

The fading outlook for iron ore is being driven by miners' investments in new projects and mine expansions around the world. But it is also being driven by China itself, whose flourishing steel industry, currently the world's largest iron-ore consumer, may soon be producing more steel scrap, thus reducing the need to import the ore.Let's quickly summarize. We can probably expect at least another decade or so of strong growth in commodity demand from China. China isn't going away in a hurry. But the miners all know this, and have been investing accordingly. Which means there is a huge amount of new commodity supply set to come on line in the next few years. Even if everything goes right and the very strong growth in Chinese metals demand continues, this additional supply is likely to send prices lower.

"From 2015, we believe an additional industry dynamic will enter the fray: the increase in Chinese domestic scrap supplies," Credit Suisse analysts say. China's new construction and its growing consumption of metal-intensive products will provide additional fodder for domestic scrap. Worn-out cars, household appliances, construction beams and old railroad tracks—all can be melted down and put it into a furnace to produce new steel products.

"We expect prices to begin falling well below $100 a ton..." Credit Suisse says, referring to the period beyond 2015.

And this new supply will also be hitting the market at a time when some economists (read Michael Pettis, for example) believe China is running into some serious constraints in its growth model. If China was to hit a speedbump some time in the coming few years and fall into recession, there is a chance that commodity prices could collapse, with disastrous consequences for Australia. This is not necessarily a likely scenario, but it is a risk that we need to be mindful of, because Australia's economy is extremely vulnerable to such a potential shock, as we will examine a bit further below.

Australia: Living on Borrowed Time

Let's go full circle back to the terms of trade. Some of you might have read reports of a recent study by the IMF, which surprisingly concluded that Australian house prices were only mildly overvalued. The IMF argued that there were solid fundamental reasons for Australia having the most expensive property prices in the world. And one of the key reasons they cited is the massive rise in Australia's terms of trade.

You can see from the chart below that, indeed, inflation-adjusted house prices have basically increased in line with Australia's terms of trade over the past two decades.

This raises an obvious question. If you agree with the IMF's logic, doesn't this imply that house prices have to fall when the once in a generation boost to the terms of trade reverses?

Now, Australia's terms of trade has gone through long rises and falls over history without huge problems. And a decline in the terms of trade wouldn't necessarily have to be a big problem if Australia had invested the proceeds of the current boom productively. But instead, Australians have turbocharged the boom by taking on record levels of personal debt (see below), mainly to purchase houses. And the Australian banks are financing a good part of this mortgage debt not through deposits, but through a potentially unstable source of funding: the international bond markets.

So we are now left very highly leveraged, and the valuation of the biggest asset that most Australians own (their houses and investment properties) as well as their ability to service this debt (and the banks' willingness to keep extending credit) is dependent on the continuation of the commodity boom. The enormous level of personal debt means that many Australians today are highly vulnerable to potential shocks in the economy, whether from a slowdown in China, or from higher interest rates.

|

| Source: Steve Keen |

The chart below, from an excellent post at deflationite.com, shows just how unbalanced the Australian economy has become over the past two decades. You can see that in 1990, the majority of Australian bank lending was being channeled into business investment, or investment in Australia's future productive capacity. But over the past two decades, the portion of bank credit allocated to business investment has steadily shrunk. In place of this, we have seen massive growth in property-related lending, to the point where one in seven Australians today owns one or more investment properties.

In essence, Australians have been behaving as if the commodity boom and the days of easy credit will last forever. Nobody can predict the timing, but they won't. Now, that doesn't have to mean disaster, but we're kidding ourselves if we think the adjustment is going to be easy.

As Warren Buffet once said, "It's only when the tide goes out that you learn who's been swimming naked."

Monday, January 17, 2011

Is Australia living on borrowed time?

Credit Suisse this week predicted a sharp slowdown in Australia's GDP growth for 2011 and recommended selling shares in resource companies, based on their view that the Chinese economy is headed for a slowdown. It remains to be seen if they're right, but one thing is for sure; Australia's economic fortunes are more closely tied to China and its demand for commodities than ever before.

In this recent post, I argued that Australia is extremely vulnerable to a slowdown in China because of our highly leveraged households and a banking system that is overly dependent on overseas funding. Today, I would like to take things a step further and examine what is driving China's demand for commodities and for how long we can expect the commodity boom to continue. This is a complicated question, so I'm going to break it up into two posts. Today we'll look at the demand for commodities, and in a follow up post, I'll examine the supply side.

You might ask the question of what there is to worry about, since commodity prices continue to shoot through the roof. Indeed, the Queensland floods have only exacerbated this upward pressure on prices, with many coal mines flooded and supply looking like it could be restricted for some time. The chart below shows the CRB commodity price index, which has been on a very steady climb for the past six months now.

This continued rise in commodity prices is likely to push Australia's soaring terms of trade even higher still. As you can see from the chart below, we are currently enjoying the biggest boom in our terms of trade since the early postwar years. But how long can this extraordinary situation last?

Our Terms of Trade

First, some definitions are in order. What does the explosion of the terms of trade mean in English? It means that the price of the stuff we export (commodities like iron ore, coal, etc) has been rising much faster than the price of the stuff we import (finished goods like cars, flat screen TVs, etc). All other things equal, a higher terms of trade means more purchasing power for Australians, and therefore a higher standard of living.

Let's now take a look at what drives the terms of trade and try to get a handle of whether its massive rise in the past decade is sustainable. Like any other good, the price of commodities is determined by supply and demand. The demand side of the equation is what usually gets the most attention, so we'll examine that first.

China and the Demand for Commodities

The first important thing to understand here is that there has been a massive shift in the composition of demand for commodities in the past couple of decades. While industrialized economies used to be the biggest consumers of non-food commodities, that is no longer the case, as the charts below from the Brazilian miner Vale show. You can see that emerging market economies now make up more than 80% of global demand for iron ore, and two thirds of demand for nickel and copper.

To simplify the analysis, let's just look at China, because it's pretty safe to ignore everybody else. Why? Take iron ore for example, which is the raw material used to make steel. World steel production has risen by two thirds in the last decade, but 90% of this growth has come from China, according to this article.

How much longer can we expect this enormous growth to continue? Well, that's a very difficult question, because it depends on factors like the rate of urbanization in China, and the timing of when China shifts its economy from the current investment and export-led model to a more consumer-driven one. In any case, the consensus seems to be that we can expect the high growth period of China's demand for commodities to last at least another decade, since the country still has a lot of infrastructure to build to support its huge population. See more forecasts from Vale below.

One recent study from academics at ANU forecast that China would reach "peak steel intensity" -- or the peak consumption of steel per capita -- by 2024. The chart below from the RBA illustrates the similar point that China is still in an early stage of economic development that tends to be very intensive in the use of raw materials. If we assume a similar path of development to that of Japan, then China still has some way to go along the path of industrialization before its demand for steel peaks.

And this is broadly consistent with what the miners and other analysts say. As the investment bank Barclays put it in one recent report:

What Are the Risks?

Firstly, long-term economic forecasts for metals demand -- or anything else for that matter -- are little more than educated guesswork. As I noted here, economists don't exactly have a great track record at getting these things right. And this may be even more relevant in the case of China; the world has never seen such a large economy industrialize so rapidly, so we have no prior experience to base the forecasts on. So no matter how plausible these estimates sound, we should treat them with a healthy degree of scepticism, allowing for the possibility that they could turn out to be completely wrong.

Secondly, even if the bullish long-term forecasts for Chinese metals demand are correct, that doesn't mean we won't hit any speed bumps along the way. There are plenty of signs that some of the infrastructure spending going on recently in China is unproductive at best, and at worst, reflective of a speculative bubble waiting to burst.

See the chart below, for example, which shows that China is set to build 44% of the world's skyscrapers in the coming six years. One analyst calls this rush to build higher and higher skyscrapers a classic "sign of economic over-expansion and a misallocation of capital." Eerie footage of entire vacant cities, and reports of up to 64 million unoccupied houses in China (recently highlighted by the Unconventional Economist) also raise questions about the sustainability of China's boom, and have reportedly prompted some hedge funds to start betting on a crash.

So there are some big question marks on the demand side for commodities, even if we do agree with the bullish long-term picture. And a temporary collapse in demand from China could cause a lot of damage to other economies and financial markets, because very few people are prepared for it. As Albert Edwards, an investment strategist at the French bank Societe Generale puts it:

In any case, to summarize, we can be cautiously optimistic that China's demand for commodities will continue to grow for another decade or more, but there could be some very painful adjustments along the way. Having said that, we've still only looked at half the story, because it's the interaction of commodity demand with supply that determines prices and ultimately, Australia's terms of trade. What about the supply side?

This is where the story starts to get interesting. And that will be the subject of my next post.

In this recent post, I argued that Australia is extremely vulnerable to a slowdown in China because of our highly leveraged households and a banking system that is overly dependent on overseas funding. Today, I would like to take things a step further and examine what is driving China's demand for commodities and for how long we can expect the commodity boom to continue. This is a complicated question, so I'm going to break it up into two posts. Today we'll look at the demand for commodities, and in a follow up post, I'll examine the supply side.

You might ask the question of what there is to worry about, since commodity prices continue to shoot through the roof. Indeed, the Queensland floods have only exacerbated this upward pressure on prices, with many coal mines flooded and supply looking like it could be restricted for some time. The chart below shows the CRB commodity price index, which has been on a very steady climb for the past six months now.

This continued rise in commodity prices is likely to push Australia's soaring terms of trade even higher still. As you can see from the chart below, we are currently enjoying the biggest boom in our terms of trade since the early postwar years. But how long can this extraordinary situation last?

Our Terms of Trade

First, some definitions are in order. What does the explosion of the terms of trade mean in English? It means that the price of the stuff we export (commodities like iron ore, coal, etc) has been rising much faster than the price of the stuff we import (finished goods like cars, flat screen TVs, etc). All other things equal, a higher terms of trade means more purchasing power for Australians, and therefore a higher standard of living.

Let's now take a look at what drives the terms of trade and try to get a handle of whether its massive rise in the past decade is sustainable. Like any other good, the price of commodities is determined by supply and demand. The demand side of the equation is what usually gets the most attention, so we'll examine that first.

China and the Demand for Commodities

The first important thing to understand here is that there has been a massive shift in the composition of demand for commodities in the past couple of decades. While industrialized economies used to be the biggest consumers of non-food commodities, that is no longer the case, as the charts below from the Brazilian miner Vale show. You can see that emerging market economies now make up more than 80% of global demand for iron ore, and two thirds of demand for nickel and copper.

To simplify the analysis, let's just look at China, because it's pretty safe to ignore everybody else. Why? Take iron ore for example, which is the raw material used to make steel. World steel production has risen by two thirds in the last decade, but 90% of this growth has come from China, according to this article.

How much longer can we expect this enormous growth to continue? Well, that's a very difficult question, because it depends on factors like the rate of urbanization in China, and the timing of when China shifts its economy from the current investment and export-led model to a more consumer-driven one. In any case, the consensus seems to be that we can expect the high growth period of China's demand for commodities to last at least another decade, since the country still has a lot of infrastructure to build to support its huge population. See more forecasts from Vale below.

One recent study from academics at ANU forecast that China would reach "peak steel intensity" -- or the peak consumption of steel per capita -- by 2024. The chart below from the RBA illustrates the similar point that China is still in an early stage of economic development that tends to be very intensive in the use of raw materials. If we assume a similar path of development to that of Japan, then China still has some way to go along the path of industrialization before its demand for steel peaks.

And this is broadly consistent with what the miners and other analysts say. As the investment bank Barclays put it in one recent report:

The shift from metals-intensive, investment-driven growth to consumer-driven growth is likely to be gradual in China. Chinese steel consumption of about 480kg per capita for 2010 is still significantly below peak levels of 600kg-1000kg per capita seen historically in other developing economies. In addition, Indian steel consumption is growing at close to 10% per year but is still estimated to be just 60kg per capita for 2010. We see significant upside in demand for steel, steelmaking raw materials, and other metals in China and India over the next 5-10 years.So there are good reasons to expect the strong growth in Chinese demand for commodities will continue for some time yet. But there are a couple of important caveats here.

What Are the Risks?

Firstly, long-term economic forecasts for metals demand -- or anything else for that matter -- are little more than educated guesswork. As I noted here, economists don't exactly have a great track record at getting these things right. And this may be even more relevant in the case of China; the world has never seen such a large economy industrialize so rapidly, so we have no prior experience to base the forecasts on. So no matter how plausible these estimates sound, we should treat them with a healthy degree of scepticism, allowing for the possibility that they could turn out to be completely wrong.

Secondly, even if the bullish long-term forecasts for Chinese metals demand are correct, that doesn't mean we won't hit any speed bumps along the way. There are plenty of signs that some of the infrastructure spending going on recently in China is unproductive at best, and at worst, reflective of a speculative bubble waiting to burst.

See the chart below, for example, which shows that China is set to build 44% of the world's skyscrapers in the coming six years. One analyst calls this rush to build higher and higher skyscrapers a classic "sign of economic over-expansion and a misallocation of capital." Eerie footage of entire vacant cities, and reports of up to 64 million unoccupied houses in China (recently highlighted by the Unconventional Economist) also raise questions about the sustainability of China's boom, and have reportedly prompted some hedge funds to start betting on a crash.

So there are some big question marks on the demand side for commodities, even if we do agree with the bullish long-term picture. And a temporary collapse in demand from China could cause a lot of damage to other economies and financial markets, because very few people are prepared for it. As Albert Edwards, an investment strategist at the French bank Societe Generale puts it:

"In reality, China is a much more potentially volatile economy than people think. The Chinese situation is the one that could come out of nowhere because people are not considering it as a serious possibility."This sense of complacency that Edwards talks about seems particularly relevant to Australia, which -- with the help of China and some massive government stimulus -- largely avoided the global financial crisis of 2008 and has not experienced a recession for two decades.

In Edwards' view, China is a "freak economy"; its investment-to-GDP ratio is off the scale in terms of size and endurance. "In development history, Korea is the only one that got close. It then collapsed. China is basing a growth model on the most unstable part of GDP. The Chinese authorities have recognised this and are trying to steer the economy over to consumption – which is fine, but it will take a long time.

The danger, he suggests, is that China has produced such strong growth for such a long time that investors assume the process will last indefinitely. "There is too much confidence in the lack of volatility. If you get a zero or a small minus for Chinese GDP, in the great scheme of long-term development it's not a great problem. But it's a bit like investing in Nasdaq stocks in 2000 – there would be a big adjustment in price. There is an investment edifice built on the idea that China is the new growth engine of the world."

In any case, to summarize, we can be cautiously optimistic that China's demand for commodities will continue to grow for another decade or more, but there could be some very painful adjustments along the way. Having said that, we've still only looked at half the story, because it's the interaction of commodity demand with supply that determines prices and ultimately, Australia's terms of trade. What about the supply side?

This is where the story starts to get interesting. And that will be the subject of my next post.

Friday, January 14, 2011

Waiting for a sucker from Oz

My recent post on the wisdom of Australians buying up $600 million of US foreclosed properties has provoked a few interesting comments and questions by email from readers, so I thought it warranted a quick follow up. Firstly, here is what one concerned Californian reader had to say:

I'm far from an expert on these matters, but the answer to the question seems to be: "Yes, but...". The problem here is that some insurance companies have started to shy away from insuring foreclosed properties. And even with those that are willing to insure properties, you can't entirely rule out the risk of getting caught up in a complicated legal mess if the foreclosure is challenged in court. From one recent article in the Washington Post:

To conclude, yesterday's Wall Street Journal had a truly bizarre story about how residents of Salem, Massachusetts are turning to witches to exorcise the demons from their foreclosed properties. If you are hellbent on buying a property in the US, maybe you'd better look into this.

Aussies planning to be millionaires by buying anything in California should think about this. There are literally hundreds of thousands of knowledgeable CASH buyers who are NOT buying. What do we know, that Aussies don't know? First if ANY house is going to be sold, at least 5-6 insiders will get a first shot at the deal..and they will buy in hours. Any property that you see on a list...is OLD, and probably a bad deal....I think this comment speaks for itself about some of the risks involved in buying US foreclosed properties. In another recent post, I discussed an additional risk that any Australian buying US foreclosed properties needs to be mindful of: the possibility of lawsuits from previous owners of the property claiming that they have been wrongfully evicted. In response to this, one reader asked if it is possible to protect yourself from such risk through title insurance.

There is a small house across the street from me. In 2005 it cost USD $380,000...today it is for sale for $120,000. They have an auction every day. NO BUYERS! Why aren't people buying? The prices are TOO high! If you buy and rent out...what is to stop your tenant from giving notice and moving next door to the next empty house for LOWER rent? Nothing! So how many months can you handle no tenants---no rent money? Tenants are not stupid...

I look outside my window and see five For Sale signs ---all "good deals", but why haven't they sold? They were from $750-899,000 only 4 years ago. One of them wants $450k....and has been for sale for 2 years. The asking price drops every month. Why buy TODAY...when the house will be cheaper next week? I have seen some houses go through 4 buyers and sellers in 5 years. All the buyers thought they would be rich. Now you tell me why they sold? Rents are dropping every month...and my county has 22% unemployment. More than one in five adults has NO JOB!

You want to be rich? DO YOUR HOMEWORK. NO ONE wants to live near gangs. Gangs are attracted to low rents and vacant houses to squat in. Gangs move in and all house prices drop in the area. I saw an ad for the 888 company showing a newer house near Atlanta Georgia to sell to Aussies. I called a friend who lived nearby the house. There was a gang murder - two people shot one block from the house. Police have no suspects. People in gang areas will not talk...or they will be killed next.

You can see the listing on the 888 website. It's on a corner lot, in a suburb of Atlanta, Georgia....waiting for a sucker in OZ land.

I'm far from an expert on these matters, but the answer to the question seems to be: "Yes, but...". The problem here is that some insurance companies have started to shy away from insuring foreclosed properties. And even with those that are willing to insure properties, you can't entirely rule out the risk of getting caught up in a complicated legal mess if the foreclosure is challenged in court. From one recent article in the Washington Post:

The title insurance industry is maneuvering to protect itself from losses if courts rule that banks have played fast and loose with the foreclosure process. But people who buy foreclosed properties from banks may face some degree of loss despite having a title policy.In other words, title insurance should protect you, but there is so much legal uncertainty surrounding foreclosures right now that basically nobody really has a clue what is going to happen. And this is my point. Is the average Australian investor that is buying US properties sufficiently educated about these risks?

Fidelity National Financial, the largest title insurance company, is leading the industry in demanding that lenders warrant that they have followed all legal procedures in the handling of foreclosures and indemnify the title insurers if a court decides otherwise.

"They are putting on record that it is absolutely the bank's responsibility," said Susan Wachter, professor of real estate at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

But Wachter said buyers of these properties risk getting caught up in litigation among title companies, banks and possibly other entities if the foreclosure is overturned by a court. "There is still uncertainty," she said. "It's a question of litigation; it's a question of transaction costs."

To conclude, yesterday's Wall Street Journal had a truly bizarre story about how residents of Salem, Massachusetts are turning to witches to exorcise the demons from their foreclosed properties. If you are hellbent on buying a property in the US, maybe you'd better look into this.

SALEM, Mass.—There's a certain look and feel to a foreclosed home, and 31 Arbella St. has it: fraying carpet, missing appliances, foam insulation poking through cracked walls.What can I say?

That doesn't faze buyer Tony Barletta since he plans a gut renovation anyway. It's the bad vibes that bother him.

So two weeks before closing, Mr. Barletta followed witch Lori Bruno and warlock Christian Day through the three-story home. They clanged bells and sprayed holy water, poured kosher salt on doorways and raised iron swords at windows.

"Residue, residue, residue is in this house. It has to come out," shouted Ms. Bruno, a 70-year-old who claims to be a descendant of 16th-century Italian witches. "Lord of fire, lord flame, blessed be thy holy name...All negativity must be gone!"

The foreclosure crisis has helped resurrect an ancient tradition: the house cleansing. Buyers such as Mr. Barletta are turning to witches, psychics, priests and feng shui consultants, among others, to bless or exorcise dwellings.

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

Economists. What are they good for?

The American economist Dean Baker has a nice article this week titled How Many Economists Does it Take to See a $8 Trillion Housing Bubble?

Maybe they're right. But wouldn't it be nice if they at least pointed out some of the risks? In any case, next time you read an economist's prediction in the newspaper, keep in mind that most of the time, at least when it comes to predictions about the future, the experts don't have a clue what they're talking about. And they are especially bad at predicting when things might go wrong. As James Montier of the fund manager GMO said recently:

Like any other profession, there are plenty of smart people in economics. So why are economists so incredibly useless when it comes to forecasting? As Dean Baker notes in the article above, if you were looking in the right place, it wasn't hard to see that there was a major housing bubble developing in the USA in the years of 2000 to 2007, but hardly anybody raised the alarm. Here are a few possible explanations that come to mind:

In any case, it's not easy going against the flow. David Rosenburg, a highly respected American economist who is now at the Canadian investment firm Gluskin Sheff, recently spoke about how lonely it was being one of the few pessimists during the market rally in 2003-2007, when he was chief economist at Merrill Lynch, whose corporate symbol was a bull.

The answer to that question has to be many more economists than we have in the United States. Very few economists saw or understood the growth of the $8 trillion housing bubble whose collapse wrecked the economy. This involved a degree of inexcusable incompetence from the economists at the Treasury, the Fed and other regulatory institutions who had the responsibility for managing the economy and the financial system.Does any of this sound familiar? To some of us it is equally baffling that having watched what has happened in the United States and many other countries, economists at Treasury, the RBA and all the Australian banks continue to tell us that there is nothing at all to worry about in Australia.

There really was nothing mysterious about the bubble. Nationwide house prices in the United States had just kept even with the overall rate of inflation for 100 years from the mid 1890s to the mid 1990s. Suddenly house prices began to hugely outpace the overall rate of inflation. By their peak in 2006 house prices had risen by more than 70 percent after adjusting for inflation. Remarkably, virtually no U.S. economists paid any attention to this extraordinary movement in the largest market in the world.

Had they bothered, they would have quickly seen that there was no plausible explanation for this jump in prices in either the supply or demand side of the market.

Maybe they're right. But wouldn't it be nice if they at least pointed out some of the risks? In any case, next time you read an economist's prediction in the newspaper, keep in mind that most of the time, at least when it comes to predictions about the future, the experts don't have a clue what they're talking about. And they are especially bad at predicting when things might go wrong. As James Montier of the fund manager GMO said recently:

Attempting to invest on the back of economic forecasts is an exercise in extreme folly, even in normal times. Economists are probably the one group who make astrologers look like professionals when it comes to telling the future. Even a cursory glance at Exhibit 4 (see below) reveals that economists are simply useless when it comes to forecasting. They have missed every recession in the last four decades! And it isn’t just growth that economists can’t forecast: it’s also inflation, bond yields, and pretty much everything else.

|

| Source: GMO |

- Some events that impact the economy are impossible to predict; for example, the recent floods in Queensland or the 9/11 attacks.

- In every single financial bubble in history, there has been an argument that "this time is different" -- from the Dutch tulip mania of the 1600s to the Japanese "miracle economy" of the 1980s to the recent US housing bubble. These arguments often sound plausible at the time, but are later shown to be rubbish. Even very smart economists get caught up in the euphoria.

- It's not easy being a contrarian. If you forecast doom, and get it wrong, you look like a fool. If you forecast a continuation of the status quo and get it wrong, well, at least you can take comfort in the fact that you got it wrong along with everyone else. If you forecast doom and get it right, you may not get that much thanks because some people will want to "shoot the messenger".

- The economists that are most prominent in the media (mostly from banks and real estate companies) are generally paid to be bullish in order to drum up business. Do you really think an economist at an Australian bank is ever going to forecast a crash in the housing market when their profits are so dependent on massive issuance of mortgage debt? (and if you think academic economists are completely free of conflicts of interest, go see Inside Job).

"There hasn't been any evidence that there has been a housing bubble and none to suggest that one is likely," James says. "Some commentators make inaccurate and damaging comments about housing bubbles and affordability without facing consequences. While it may be an emotive story, inaccuracies can limit housing investment and prevent supply from adjusting to higher demand."It might just be my imagination, but Mr James sounds a little defensive.

In any case, it's not easy going against the flow. David Rosenburg, a highly respected American economist who is now at the Canadian investment firm Gluskin Sheff, recently spoke about how lonely it was being one of the few pessimists during the market rally in 2003-2007, when he was chief economist at Merrill Lynch, whose corporate symbol was a bull.

I recall all too well that 2003-07 bear market rally — yes, that is what it was... It was a classic bear market rally, and did last five years. I was forever skeptical because what drove that bear market rally was phony wealth generated by a non-productive asset called housing alongside widespread financial engineering, which triggered a wave of artificial paper profits. I knew it would end in tears … sadly, I didn’t know exactly when. I was constantly defensive in my investment recommendations at the time and there was a huge price to be paid for being bearish when there is a bull on your business card, trust me on that one.That's it for today. Next time, we'll take another look at China, the commodity price boom and Australian house prices. Just remember that I don't know what I'm talking about either...

Sunday, January 9, 2011

Why foreclosure-gate matters

In my last post we took at look at Australia's latest investing fad: buying up foreclosed properties in US states like California, Nevada and Florida. We've already examined how anybody who thinks this is a good idea probably needs their head checked, but there is one additional risk that I didn't even mention: the risk of getting sued by the previous owner of a property that you've bought if he or she claims that they were wrongfully thrown out of their house.

On this front, a Massachusetts court delivered a very important decision last week that could have huge implications for the US housing market and mortgage securitization. From the NY Times:

During the boom years leading up to 2008, American banks packed together millions of mortgage loans, and sliced and diced, or "securitized" these into thousands of securities called MBS. To create an MBS, the banks would first sell the loans to a trust, which then sold bonds backed by those mortgages to investors all over the world. But there was a minor problem. In their rush to issue as many of these securities as possible and pay themselves gargantuan bonuses, the bankers didn't bother to do the paperwork properly, and now it's unclear who actually holds the mortgage notes. Oops.

Of course, at the time these loans were made nobody ever thought this would be a problem because, as we know well in Australia, house prices double every 7 years and borrowers never default on their mortgages. Now, a few years later, there are millions of Americans delinquent on their loans.

"Foreclosure-gate" started brewing late last year when it became evident that having stuffed up the paperwork, many of the banks had hired thousands of "robo-signers" to write false affadavits claiming that they had reviewed the loan documents (which they hadn't even seen). These affadavits were then being used to evict people who had stopped paying their mortgages.

So, the court case above puts an end to this kind of nonsense from the banks, at least in Massachussets. Until they get their paperwork in order (if that is even possible) they will have to stop turfing people out of their homes. The real estate experts cited here here say that this delay in the processing of foreclosures would be a good thing for the housing market.

But loan restructurings are tricky, because if the lenders offer attractive loan modification terms to delinquent borrowers, then even people who are able to pay their mortgage will start "strategically" defaulting in order to become eligible for debt forgiveness. And this would probably make some lenders insolvent. On top of this, securitization makes the whole process even more complicated because there are so many parties involved. In an MBS deal, there are strict contractual limits on loan modifications, which usually can't be changed without the consent of 100% of the MBS holders, who could number in the thousands and are usually spread all over the world. Obviously getting all these parties to agree is pretty much impossible.

In the meantime, there could be enormous potential for chaos, because the Massachusetts legal decision is going to be followed by waves of lawsuits in other states all over America. Felix Salmon of Reuters has a great post addressing this issue which I will quote at length from:

On this front, a Massachusetts court delivered a very important decision last week that could have huge implications for the US housing market and mortgage securitization. From the NY Times:

The highest court in Massachusetts ruled Friday that U.S. Bancorp and Wells Fargo erred when they seized two troubled borrowers’ properties in 2007, putting the nation’s banks on notice that foreclosures cannot be based on improper or incomplete paperwork. Concluding that neither institution had proved it had the right to evict the borrowers, the Supreme Judicial Court voided the foreclosures, returning ownership of the properties to the borrowers and opening the door to other foreclosure do-overs in the state.To explain why this is important, we have to go right back to the root of the global financial crisis of 2008, which can be found in the securitization of US subprime mortgages.

During the boom years leading up to 2008, American banks packed together millions of mortgage loans, and sliced and diced, or "securitized" these into thousands of securities called MBS. To create an MBS, the banks would first sell the loans to a trust, which then sold bonds backed by those mortgages to investors all over the world. But there was a minor problem. In their rush to issue as many of these securities as possible and pay themselves gargantuan bonuses, the bankers didn't bother to do the paperwork properly, and now it's unclear who actually holds the mortgage notes. Oops.

Of course, at the time these loans were made nobody ever thought this would be a problem because, as we know well in Australia, house prices double every 7 years and borrowers never default on their mortgages. Now, a few years later, there are millions of Americans delinquent on their loans.

"Foreclosure-gate" started brewing late last year when it became evident that having stuffed up the paperwork, many of the banks had hired thousands of "robo-signers" to write false affadavits claiming that they had reviewed the loan documents (which they hadn't even seen). These affadavits were then being used to evict people who had stopped paying their mortgages.

So, the court case above puts an end to this kind of nonsense from the banks, at least in Massachussets. Until they get their paperwork in order (if that is even possible) they will have to stop turfing people out of their homes. The real estate experts cited here here say that this delay in the processing of foreclosures would be a good thing for the housing market.

If the slowdown continued through this month and into the spring, it could be a boost for the economy. Reducing foreclosures in a meaningful way would act to stabilize the housing market, real estate experts say, letting the administration patch up one of the economy’s most persistently troubled sectors. Fewer foreclosures means that buyers pay more for the ones that do come to market, which strengthens overall home prices and builds consumer confidence in housing.This is the optimistic view. If it becomes harder for lenders to foreclose, then they might become more willing to restructure loans instead (for example cutting the interest rate on the loan and/or reducing the principal that has to be repaid), which is probably the only eventual way out of this mess. At the end of the day, the banks are going to have to take a hit for making stupid loans that were never likely to be repaid.

But loan restructurings are tricky, because if the lenders offer attractive loan modification terms to delinquent borrowers, then even people who are able to pay their mortgage will start "strategically" defaulting in order to become eligible for debt forgiveness. And this would probably make some lenders insolvent. On top of this, securitization makes the whole process even more complicated because there are so many parties involved. In an MBS deal, there are strict contractual limits on loan modifications, which usually can't be changed without the consent of 100% of the MBS holders, who could number in the thousands and are usually spread all over the world. Obviously getting all these parties to agree is pretty much impossible.

In the meantime, there could be enormous potential for chaos, because the Massachusetts legal decision is going to be followed by waves of lawsuits in other states all over America. Felix Salmon of Reuters has a great post addressing this issue which I will quote at length from:

The legal craziness that this decision sets in motion is going to be huge, I’m sure. Anybody who was foreclosed on in Massachusetts should now be phoning up their lawyer and trying to find out if the foreclosure was illegal. If it was — if there was a break in the chain of title somewhere which meant that the bank didn’t own the mortgage in question — then the borrower should be able to get their deed, and their home, back from the bank. This decision is retroactive, and no one has a clue how many thousands of foreclosures it might cover.This could get very ugly.

Similarly, if you bought a Massachusetts home out of foreclosure, you should be very worried. You might not have proper title to your home, and you risk losing it to the original owner. It might be worth dusting off your title insurance: you could need it. And if you ever need to sell your home, well, good luck with that.

Going forwards, every homeowner being foreclosed upon will as a matter of course challenge the banks to prove that they own the mortgage in question. If the bank can’t do that, then the foreclosure proceeding will be tossed out of court. This is likely to slow down foreclosures enormously, as banks ensure that all their legal ducks are in a row before they try to foreclose.

What’s more, courts in the other 49 states are likely to lean heavily on this decision when similar cases come before them. The precedent applies only in Massachusetts for now, but it’s likely to spread, like some kind of bank-eating cancer.

If a similar decision comes down in California, which is a non-recourse state, the resulting chaos could be massive. People who are current on their mortgage and perfectly capable of paying it could simply make the strategic decision to default, if and when they find out or suspect that the chain of title is broken somewhere. They would take a ding to their credit rating, but millions of people will happily accept a lower credit rating if they get a free house as part of the bargain.

The big losers here are the banks — of course — as well as investors in mortgage-backed securities, including of course Fannie and Freddie, a/k/a the US taxpayer.

Saturday, January 8, 2011

On Australians buying US property...

With Australian property prices looking very toppy and the Aussie dollar going through the roof, the latest delusional investing fad in Australia appears to be snapping up foreclosed US properties. I've been hearing stories about this a while now, so I thought I'd look into it a bit. Firstly, in case you missed the story in The Age last week, here's a little extract to set the scene:

What could possibly go wrong?

The Age quotes a Byron-Bay based buyers agent called 888 US Real Estate, which according to its website charges a "committment fee" of $380 and then a commission of $3,420 for each property purchase it handles for the Aussie battlers trying to realise their dreams. But 888 US Real Estate is just one of a handful of organizations that are sprouting up like weeds to flog US property to unsuspecting Australian buyers. Here are just a few of the ridiculous sales pitches made on some of these websites.

But for now, we should concede that some of the claims they make are accurate. It is indeed true that in many parts of the US today, you can buy a house for less than the price of a new car in Australia, or for less than the average deposit on a house in most Australian cities. Which raises another question. There are a lot of very smart American investors with a lot of money to burn. If properties in the US are such a bargain, why is it that many of these American investors still don't want to touch the property market with a ten foot pole?

Miami Vice

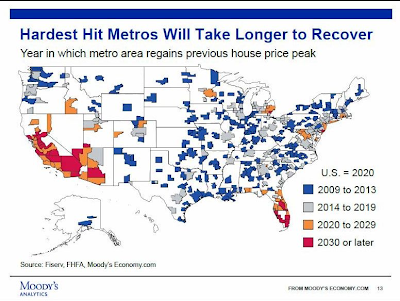

I'm not going to go into detail about what an absolute debacle the US property market is today, but let's just take a look at an interesting graphic in a recent report from the ratings agency Moodys. Moody's notes that there is still a massive surplus of housing inventory on the market, and that foreclosures and defaults are still skyrocketing in many parts of the country. You can see below that there are significant parts of California, Nevada, Arizona and Florida, where Moody's doesn't expect the housing market to fully recover until 2030. Yes, that's still two decades away.

And guess where the property spruikers are trying to talk Australians into buying investment properties? You're right. Places like California, Nevada, Arizona and Florida. Here's are a couple of listings in Florida from My USA Property:

Now, on the surface, property prices in Florida look like a real bargain, since they've already fallen around 45% in Miami and more than 40% in Tampa, as you can see below.

Unsuspecting Suckers

But there's no guarantee that prices are ever going to return to these peaks again, at least for a very long time in some of these areas. In fact, one recent study (which I might examine in more detail when I get the chance) argues that the housing bust may have created new types of "declining cities" across the USA -- certain cities which grew rapidly in the boom, attracting huge population inflows and investment -- but which are now facing the prospect of decades of stagnation thanks to a vicious circle of falling house prices, declining populations, rising vacancies, and increasing crime rates.

Some Australian investors are already finding this out the hard way. From the above story in The Age:

Dumb Things

Without a doubt, there are going to be some good investment opportunities in some parts of the US. But how the hell are you going to identify them from Australia, and can you really trust the clowns at places like 888 US Real Estate to pick the winners for you?

And that's not to mention the myriad of other problems involved with buying property in the US, which the property spruikers gloss over, but include:

It's time to wrap this up. Let's end with an appropriate Aussie classic from Paul Kelly.

AUSTRALIAN property investors risk losing hundreds of millions of dollars after snapping up thousands of US housing bargains at forced-sale prices, experts have warned.Another article from The Age tells the story of the following couple:

Emboldened by the soaring local dollar, Australians invested about $600 million on US residential property last year, according to the Washington-based National Association of Realtors, as overseas buying of US housing doubled.

But consumer advocate Neil Jenman predicts that thousands of Australians will lose their money after unwittingly buying undesirable property.

''It's going to be a calamity, for sure and certain,'' he says.

CLEANERS Ana and Miguel Canepa never imagined when they fled to Australia as refugees they would one day be landlords of four rental homes. But the residents of St Albans in Melbourne's outer north west are living the Australian dream, having last week signed contracts to buy their latest investment property. And it only cost them $A44,117.

That is because the three-bedroom house is in the US city of Phoenix in Arizona.

The couple, originally from El Salvador, have never been to Phoenix. But they already own two other homes purchased there this year for $A41,000 and $A52,100, as well as a fourth rental asset in Melbourne.

Real estate specialist Kevin Walters, who arranged the Canepa's purchases, will next month lead a shopping tour for 10 Australians and a tax firm that advises self- managed superannuation holders. They will visit Phoenix and Las Vegas, the foreclosure capital of the US.

''You can buy a house in the US for the cost of a deposit here,'' he says. ''Clients can purchase property in just two days, it's that easy. The only exception is that we don't have a lender for them at the moment, so they buy in cash.'' Mr Thomas says he gets rental returns of 16 per cent on his US assets, compared to about 3 per cent for his Australian properties. ''It doesn't seem a risk at all to me,'' he says.

What could possibly go wrong?

The Age quotes a Byron-Bay based buyers agent called 888 US Real Estate, which according to its website charges a "committment fee" of $380 and then a commission of $3,420 for each property purchase it handles for the Aussie battlers trying to realise their dreams. But 888 US Real Estate is just one of a handful of organizations that are sprouting up like weeds to flog US property to unsuspecting Australian buyers. Here are just a few of the ridiculous sales pitches made on some of these websites.

- "It's no secret: USA property investment gives you a 10-20% net return... Even after your expenses are paid you will still make money with My USA Property"

- "Once American banks start lending again, the USA market will recover. So you’d be wise to invest in an undervalued market now since every Australian dollar buys more" (My USA Property)

- "When you say “Go!” you set the wheels in motion for an exhilarating ride as your property grows in value giving you the possibility to create enough cash to fund the rest of your life in a few short years. Call us now!" (888 USA Real Estate)

But for now, we should concede that some of the claims they make are accurate. It is indeed true that in many parts of the US today, you can buy a house for less than the price of a new car in Australia, or for less than the average deposit on a house in most Australian cities. Which raises another question. There are a lot of very smart American investors with a lot of money to burn. If properties in the US are such a bargain, why is it that many of these American investors still don't want to touch the property market with a ten foot pole?

Miami Vice